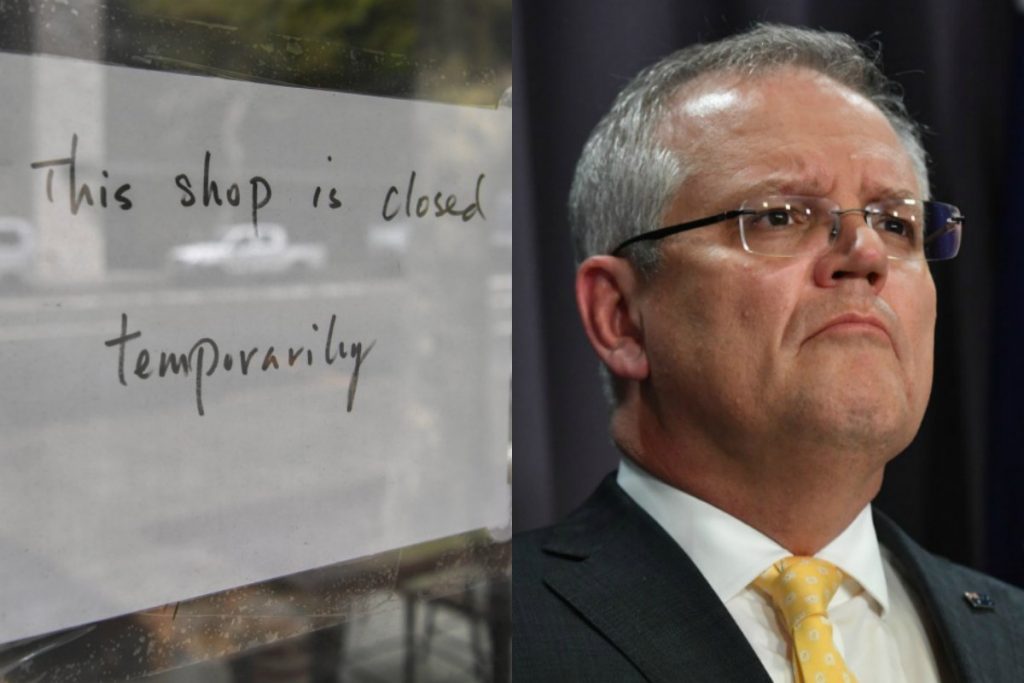

The government has stepped in to pay a portion of the newly-unemployed's wages. But this isn't such a new idea.

Wage subsidy… living wage… income guarantee…

Whatever you call the Federal Government’s JobKeeper program, it’s got everybody talking. If you missed the details, they are:

“Up to six million workers will receive $1500 fortnightly payments under a $130bn JobKeeper scheme… to keep businesses open throughout the COVID-19 economic crisis and protect hundreds of thousands of jobs.”

It’s been almost universally well received. It provides a strong social safety net for those suddenly unemployed while also providing incentives to business to retain their employees.

The thing is, this JobKeeper package vaguely resembles the kind of policy a few people have been advocating for recently – most notably, former Democratic Presidential candidate, Andrew Yang.

According to New York Magazine:

“Throughout his campaign, Yang pushed the idea of a universal basic income (UBI) — $1,000 a month for every American adult — to help reinvigorate the middle class and to offset job displacement due to automation.”

Not such a new idea

You see, the idea of more jobs being at risk due to automation isn’t new. In fact, in the last year of President Obama’s administration, the White House submitted an economics report to congress. The White House Council of Economic Advisors used some complicated algorithms to examine how many low-paying American jobs (less than $20 per hour) were under threat of being replaced by automation.

The answer? 62%.

The most well-known report on this topic came from Oxford University in 2013 which predicted that 50% of today’s jobs could be replaced by robots over the next 20 years.

So who came up with the idea in the first place? Apparently the idea emerged over 100 years ago according to Adam Creighton from The Australian:

Philosophers and economists have promoted the idea for centuries but it has always gone nowhere. Now the prediction by economist John Maynard Keynes back in 1930 appears to be coming true: within 100 years immense wealth would emerge alongside mass de facto unemployment, “due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour”.

Obviously a UBI would help all these newly unemployed people survive without a job – hence the government’s JobKeeper program – but we’ve already seen a similar scheme in place overseas.

Back in 2017 a Canadian province begun a trial of UBI to 4,000 participants. The plan saw single participants receive up to $16,989 over the course of a year while couples received up to $24,027. The jury is still out as to its effectiveness.

Farther afield, Switzerland held a referendum in 2016 on a UBI (of about 2500 Francs per month) and around 77% of the population rejected it.

Not so fast

Here’s where things get contentious. The concept of a UBI as a short-term measure to act as a social safety net is clearly of significant value. But as a long-term or permanent program? Here I’m not so sure. The biggest question in my mind would be: why reward people without incentive? If people are going to be paid to do nothing, wouldn’t people default to being lazy and not contributing?

One comeback to this argument comes from Charles Murray, from the American Enterprise Institute, who says: “Yes, some people will idle away their lives on UBI but that is already a problem.”

Hardly reassuring. The argument “Well people do that now” is hardly a stirring reason to change to something that does the exact same thing.

That said, what is the alternative? If low-paying jobs are eliminated, how do the low-skilled survive? As Murray writes: “It takes a better imagination than mine to come up with new blue-collar occupations that will replace more than a fraction of the jobs that taxi drivers and truck drivers will lose when driverless vehicles take over.”

The question for Australia now appears to be: is UBI the long-term answer? Clearly there was a moral imperative to protect the suddenly unemployed during the midst of a global pandemic, but when things return to normal what happens?

And, if the economy doesn’t recover quickly, we could be faced with the harrowing possibility of many people being unemployed for a significant amount of time.

Perhaps a UBI may hang around longer than we think.